Oh, that nagging feeling that you are not good enough, that you didn’t deserve praise, that you just got lucky, that you don’t fit in…

Does this line of thought sound somewhat familiar?

„I feel like a fraud. What gives me the right to be in the position I am in now? I don’t have the abilities needed, I’m not competent enough, someone would be way better at this. It’s just a matter of time when everybody realizes this. And all the accomplishments I’ve made? Honestly, I was lucky. Besides, everybody could do it.“

Most people experience some self-doubt when facing new challenges. It’s completely normal, especially when we work on something new. However, when self-doubt is there almost constantly, no matter how much you have accomplished, it’s possible that you are experiencing something called the imposter syndrome.

The imposter syndrome is a feeling of chronic insecurity and doubt about your abilities, despite plenty of contrary evidence. It’s often accompanied by fear that you will be exposed as a fraud, or that your accomplishments are just a matter of luck, not your talent or abilities.

The imposter syndrome is very common among high achievers, who often have massive expectations from themselves and lean toward perfectionism. Research shows that around 20% of highly successful people experience this state very often, while 70% of people experience it at least once in their lifetime.

People who experience the imposter syndrome tend to:

- attribute their accomplishments to luck or some external reasons, rather than their ability

- believe that every task they take has to be done perfectly and rarely ask for help

- be convinced that people are overestimating their abilities

- feel like they don’t deserve success or praise for their achievements, and believe that other people are somehow deceived into thinking otherwise

- fear of being’discovered as a fraud’, that everybody will find out how incompetent they are

It’s not surprising, then, that the imposter syndrome is often accompanied by anxiety, perfectionism, and sometimes depression.

Where Does the Imposter Syndrome Come From? What Causes It?

Cultural influence

More and more people are experiencing imposter syndrome, and it comes as no surprise. Our society puts a huge emphasis on achievement. In our culture, there is often a pressure to “be the best version of yourself”, to accomplish, work hard, be competent and confident, etc. This can trigger self-doubt, especially when the majority is participating in this game. You see people around you and on social media who are always busy, accomplishing something, moving ahead, people who seem to know what they’re doing with their lives. Maybe they do, maybe they don’t. What is easy to forget is that people tend to try to present themselves in the best light possible, even if that is not an accurate picture. When we overlook this, when we compare our whole story, our ups and downs, with someone’s highlights only, it’s easy to doubt ourselves, wondering if our abilities are enough.

Certain environmental factors can contribute to the imposter syndrome. A sense of belonging fosters confidence; genuine support can do wonders for our trust in ourselves. If you are part of a group where there are certain stereotypes about competence, where there is less support and positive reinforcement, or you feel like you don’t belong, there is a higher chance of developing signs of imposter syndrome. Studies show that imposter syndrome is more common among racial and ethnic minorities.

Childhood experiences

People who struggle with imposter syndrome can come from different family dynamics. They are often children of parents who value and praise achievement above everything else, and who believe that criticism is the best motivation. The imposter syndrome often has its roots in families where there is a lack of support, where the child gets harshly criticized for failure, but receives little to no praise for success because the parent believes that success is something that should be a norm, not something the child should be applauded for. Additionally, it is common for people who come from families where they always had to do what was expected from them, and they worked especially hard to please others.

In such circumstances, the message the child receives is something along the lines of: “I should always achieve, excel, be competent. It’s somehow never enough, but I have to keep trying. I am not enough the way I am, so I must work hard to compensate”. This becomes a perpetuating cycle in adulthood.

If this sounds like you, it is possible that, since you “learned” very early on that mistakes will be met with criticism, followed by feelings of shame, guilt, and unworthiness, you try to avoid such feelings by mechanisms that helped you in the past, such as working hard, perfectionism, trying to convince others that you’re a smart, competent person, etc. However, since you’ve rarely been praised for your abilities, it’s difficult for you to internalize success and genuinely believe that you are capable. Generally, the imposter syndrome is commonly a result of seeking self-esteem by trying to live up to an idealized image, to compensate for feelings of insecurity and self-doubt.

Beliefs about intelligence and success

Imposter syndrome sometimes occurs even without the above-mentioned family dynamic. For example, research shows that academic success in childhood in combination with parents and teachers who emphasized your natural intelligence, as well as a biologically higher susceptibility to anxiety, can contribute to developing the imposter syndrome later in life.

A common scenario is this: things went smoothly for you in elementary and high school, you didn’t have to work hard and people around you adored your intelligence. But in college, or on a new job, where there are higher demands, you start struggling. Now that challenges are bigger and you need to put in much more work, you may start doubting your natural intelligence and your abilities, feeling like you don’t have what it takes to be successful after all. Because you learned that “how intelligent you are” = “how little you struggle with challenges”, when things are not so easy and you need to put in extra effort, you may start thinking of it as evidence that you may not be as smart and capable as you and/or others thought you were.

Indeed, studies explain this phenomenon. For example, research showed that people who think of intelligence as a fixed trait tend to follow “performance goals”, which means that they are primarily motivated by the wish to prove their intelligence and capability. This kind of thinking is often followed by shame, anxiety, and fear that others would see them as incompetent. On the other hand, people who see intelligence as a malleable quality are motivated by “learning goals” – their primary aim is to increase their knowledge and skills. These individuals react to failure in a more resilient way and rarely feel inadequate.

How to Deal With the Imposter Syndrome

Fortunately, there are ways to beat this uncomfortable state. If the imposter syndrome is negatively impacting your health and your ability to properly function, it is important to seek professional help. Additionally, here are a few tips to possibly help you get out of your way, decrease anxiety surrounding (dis)trust in your abilities, and take ownership of your success.

1. Know that it’s not just you.

You may be feeling like everyone except you knows exactly what they’re doing, but that is not true. This feeling is common in the general population, but especially among high achievers.

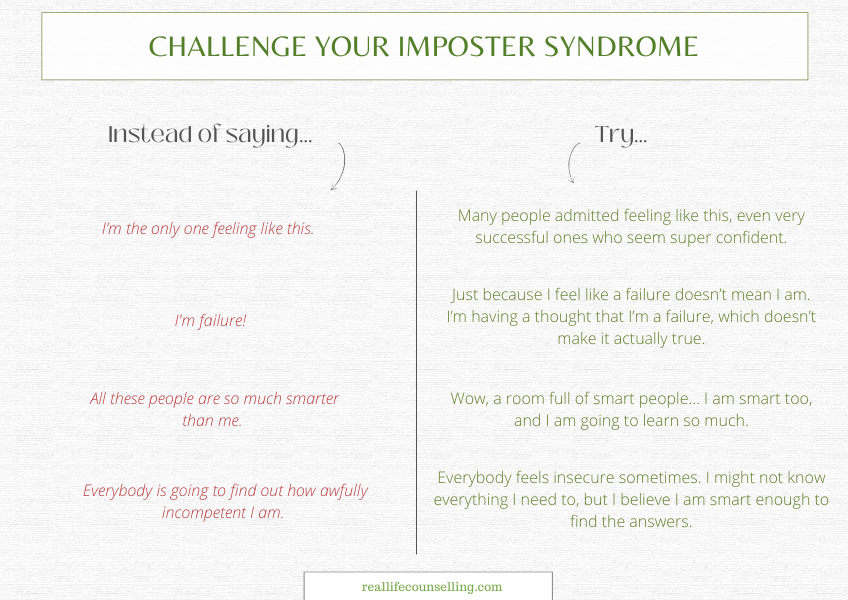

2. Separate thoughts and feelings from facts

Your feelings are always valid. There is no “You shouldn’t feel like this” or “It’s ridiculous to feel this way”. You feel what you feel, and all feelings are okay. Emotions carry important information, they are there for a reason. However, that reason is not always something in your environment. Thoughts and feelings are internal events that don’t have to be (and often are not) 100% based on reality. Many times, our feelings come as a result of interpretations that are influenced by our past experiences, assumptions and expectations, fears, and insecurities.

So, your feeling incompetent is not proof of your incompetence. You’re having a thought about being incompetent, which can come from a place of insecurity, fear, and anxiety, but it is not a reflection of your objective abilities.

3. Refrain from Comparison

Comparing yourself to others is a shortcut to feeling frustrated, insecure, and anxious. And not only does it usually leave us feeling awful, but it’s also pointless. How does comparing someone’s “spotlights” with your “behind the scenes”, which is how we usually compare, make sense? We are all different people with different “starting points”, different backgrounds, preferences, abilities, traits, and entirely different lives. Perhaps a better choice is to, instead, invest that energy into learning and growing, in your way.

4. Change the spotlight of your attention and reframe how you look at the situation

Someone once wisely said that the difference between misery and happiness depends on what you do with your attention.

Instead of emphasizing all the mistakes you’ve made or the fear of being exposed, you can do many other, more productive things with your attention. For example, you can make an effort to re-focus from trying to appear confident and competent and that way possibly prevents others from “finding out” what a fraud you are, to learning from others and your mistakes, building your skills, and doing the best you can (whatever that “best” is for you – don’t set unrealistically high expectations!). Or, you can turn your attention to gratitude, for all the great things, people, and experiences you have in your life. Or you can focus on catching yourself when you’re being overly critical toward yourself and challenge this kind of self-talk.

Shifting your attention like this is not easy, but it’s essential. Insight itself is important but doesn’t do much without applied, real-life work on changing the existing patterns.

Another interesting thing you can do with your attention is test your confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is the tendency to find evidence that supports beliefs you already have, overlooking or discounting the evidence that is contrary to this belief. Your imposter syndrome uses confirmation bias to convince you that you are not capable, making you see your mistakes and shortcomings, and overlooking or downplaying contrary evidence – your achievements.

How about you trick your imposter syndrome by playing the same game by testing its weapon, but in the opposite direction? Actively work on finding evidence that you are, in fact, intelligent, talented, successful, and good at what you do. Notice and write down big and small wins, remember and accept compliments and recognitions, and be thorough at finding evidence in favor of your abilities. With consistency, you may be surprised at how much your perception can shift.

5. Remind yourself that you don’t have to be perfect.

Yes, you may believe that you have to be. But objectively, nobody is, and that is perfectly okay. You are a unique human. Imperfect and enough.

Dealing with the imposter syndrome has nothing to do with minimizing mistakes and maximizing achievement, and everything to do with how you relate to yourself. So, it’s a process, it takes work, but it pays off.

In the end, here is just a gentle reminder. None of us:

- have it all together

- is 100% confident all of the time

- have never made a mistake

- is perfect

It’s called being human. It’s relatable. And it’s beautiful.

Interested in learning more about coaching or therapy? Contact us today.

Interested in learning more about coaching or therapy? Contact us today.

Sources:

Bravata, D. M., Watts, S. A., Keefer, A. L., Madhusudhan, D. K., Taylor, K. T., Clark, D. M., Nelson, R. S., Cokley, K. O., & Hagg, H. K. (2020). Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: a Systematic Review. Journal of general internal medicine, 35(4), 1252–1275. Online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7174434/

Langford, J., & Clance, P. R. (1993). The imposter phenomenon: Recent research findings regarding dynamics, personality and family patterns and their implications for treatment. Psychotherapy: theory, research, practice, training, 30(3), 495.

Sherman, R. O. (2013). Imposter syndrome: When you feel like you’re faking it. American Nurse Today, 8(5), 57-58.

Palmer, C. (2021, June). How to overcome impostor phenomenon. Monitor on Psychology, 52(4). http://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/06/cover-impostor-phenomenon. Online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/06/cover-impostor-phenomenon